Dietetics

Food is a basic need of the body. The body’s ability to change food into energy and nutrients that fuel the body’s work (e.g. walking, talking) is amazing. Also, for many of us, food is an essential part of our social lives.

Yet for people with cancer, the relationship with food and eating can change. This can happen due to where the cancer (or tumour) is or how it may change your appetite. Sometimes, the treatment for cancer can cause symptoms that put you off eating. These changes in appetite and eating can be distressing for you and your family or friends. Of course, you might not have any of these problems but may still worry about eating the ‘right’ foods. It can be helpful to think about any changes or difficulties you have with food or eating.

The information on these pages can then help you to take care of your food intake and nutrition by yourself. But if you are struggling to manage on your own you can ask a Dietitian for advice. Dietitians and Support Workers can see you if you stay on a ward at the Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre (or at your local hospital). Or you can ask your GP to refer you to see a Dietitian in a local clinic.

You'll find answers to any questions you may be asking below.

Site of cancer

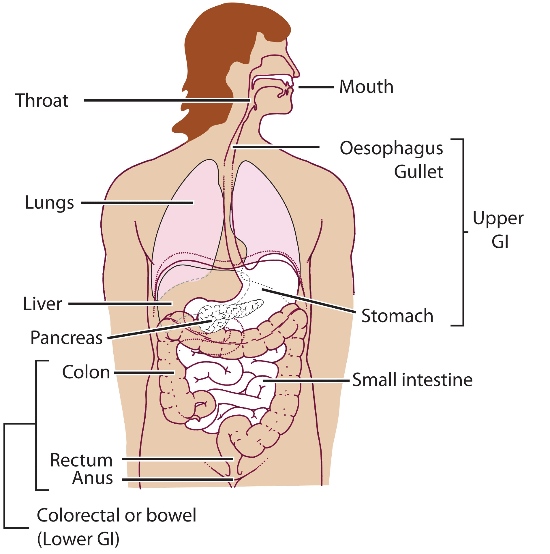

This picture shows the route that food takes as it passes through our bodies. The name of this route is the gastrointestinal tract or GI tract for short. The mouth, oesophagus (or 'gullet') and the stomach make the top parts of this tract. If your tumour is in any of these parts then the ability to eat normal foods may change. For example, you may find it hard to chew or swallow your food.

The small bowel and large bowel make up the lower parts of the tract. There can be changes in your body’s ability to soak up and use nutrients from your food if the cancer is here.

Effect of cancer on the body

But it's not only cancer in this tract that can upset the balance of your normal intake. Some cancers here or in other parts of the body can change your normal hunger and fullness signals. So sometimes you no longer feel hungry even when you haven’t eaten in a while. Or you can feel full after eating only a small portion.

Cancer treatments

The treatments for any cancer can sometimes make eating difficult. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery or immunotherapy can cause symptoms such as:-

- Feeling sick (nausea) or being sick

- Changing the way food tastes

- Changing to your bowels (diarrhoea or constipation)

- Pain

- Tiredness.

You might also be eating less if you are anxious or worried, or if you are finding shopping or cooking difficult.

If you eat less food, the body doesn't get the fuel it needs to do its normal functions. This means you will have less energy and feel less active. But the body needs fuel for its basic functions (such as the heart beating) and it must get this fuel from somewhere. So it may begin to break down your fat and muscle stores to make energy to fuel these functions. This loss of fat and muscle leads to weight loss.

Weight Gain

Sometimes you may gain weight during cancer treatment. Some hormonal or steroid treatments can cause weight gain. Changes in your lifestyle during treatment can also be a cause. For example you may find that you are too tired to do normal activities such as gardening or going to the gym. Eating a healthy balanced diet may help to control your weight. Keeping as active as you can may also help you control your weight.

Where can I get more help?

- Macmillan Cancer Support - Eating well and Keeping active

- Macmillan Cancer Support - Changes in weight

Think about your normal weight

Is it considered 'healthy? What is a 'healthy weight'? When you stand (or sit) on scales, you are weighing all the parts of your body:

- Lean body mass – this is the amount of bodyweight that isn’t fat e.g. organs, skin, bones, muscle mass and body water

- Body fat.

A common measure of a healthy weight is Body Mass Index’ or BMI. This measure takes your height into account for your weight. Generally, a BMI between 20-25 suggests healthy storage of both fat and muscle.

A BMI under 20 may show low stores of both fat and muscle.

BMI over 30 may show higher fat stores (but can also be high in a person who has a lot of muscle

Weight changes usually show changes in fat, muscle mass and/or body water. Dieting or ‘slimming’ is when we try to lose some of our fat stores. Weight loss in cancer is usually a loss of both fat and muscle stores. This can leave you feeling tired or weak and can affect recovery from your treatment.

Your weight changes from day to day due to normal changes in fluid (like drinking lots of fluids or passing lots of urine (peeing lots!). This will usually be a few pounds difference in your weight. Unintentional loss of fat and muscle will show as bigger loss. If this bigger loss happens over a short period of time then you may be at risk of malnutrition.

Malnutrition means ‘poor nutrition’ and can refer to both:

- Undernutrition when you don’t get enough nutrients

- Overnutrition when you get more than you need.

Weight loss and the loss of fat and muscle reserves is an example of undernutrition.

How do I know if I’m at risk of malnutrition?

The ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ or ‘MUST’ is a quick measure of your risk. To complete this tool you need to know your current weight, your previous weight and your height. You can enter these measurements into an online ‘MUST’ screening tool here.

This website also has useful hints and tips on how you can lessen your malnutrition risk.

Where can I get more help?

You may wonder if there are certain foods you should stop eating. Or if you should start eating others to cure your cancer or stop tumour growth. There are often claims in the media that eating certain foods can cure you.

The internet also has lots of information advising you on what you should (or shouldn’t eat). Cancer Research UK has guidance on looking for information on the web as well as up to date information on some alternative therapies. Reading through the cost, side effects and evidence of use may help you decide if you wish to follow the advice. Sadly, there is little evidence to suggest that any food can stop or slow tumour growth in humans.

There is evidence that meeting your daily nutrient needs can help to keep you well during cancer treatment. You can meet your nutritional needs with a balance of:

- Macronutrients (proteins, fats, carbohydrates)

- Micronutrients (vitamins and minerals).

The government guidelines for healthy eating can advise you on how to get this balance. There is also evidence that shows that following these guidelines can prevent some types of cancer occurring. But if you are eating less than what's normal for you then following this advice may not be helpful.

Have a look at the How can I eat well when my cancer or treatment is stopping me? section.

Food Safety

If you are on chemotherapy then you may be at greater risk of infection. Food can be a source of infection so it’s important to make sure you are keeping safe when storing, preparing and eating foods. One simple piece of advice is to always wash your hands before eating. Food Standards Scotland have lots more advice on food safety. You should choose your normal foods unless your team has advised you to change anything.

Certain side effects of your cancer treatment may change your food intake or what you want to eat. Let the team looking after you know if this happens. They may prescribe you medicine which can improve or stop these symptoms.

Some of the symptoms you may experience which could impact on your food intake are:

Loss of appetite

Lack of appetite means a loss of interest in food. So if your favourite meal has been cooked, you may only pick at it. If you feel able, a short walk before a meal to boost your appetite may help. Try and eat when you feel at your best; for many people, this can be the first part of the day and if this is the case try and have a good breakfast and your main meal at lunchtime. For others, it may be at the end of the day or even during the night.

Changes in taste

You may experience changes in your taste during cancer treatment. It can be common to go off foods like chocolate, meat and coffee as they can taste bitter or metallic and sweet foods can taste very sweet. For some people, the taste is sharper and for others the sense of taste is lost. Finding foods that suit you may be a case of trial and error. For example, fish and chicken may replace red meat in your diet. Using fruit flavours for puddings helps combat the sweetness of some foods (fruit pies, mousses and yoghurts). But be careful with citrus flavours (e.g. lemon, grapefruit) if you have a sore mouth. Serving cold puddings straight from the fridge helps to make them less sweet. Taste changes are often temporary so try reintroducing foods every few weeks.

Feeling full quickly

It may be that you sit down to a meal and eat only a few mouthfuls and then feel full. This can be distressing for you and any family or friends who are preparing meals for you. Rather than having three meals per day you can try taking small meals or snacks more often. Doing this may allow you to increase the total amount of energy (calories) and other nutrients going into your body. It is important to drink plenty. But avoid taking a drink like tea, coffee or water (which have no energy or calories) before mealtimes. This can begin to fill up your stomach making you feel full and may put you off your meal.

Weakness and fatigue

Feeling tired means that you may be less likely to want to shop for or prepare meals. It can help to ask someone to help with shopping and cooking or to use ready meals (chilled, tinned, frozen). Sometimes, you may feel too tired to eat foods that someone else has prepared. It may be useful to note times of the day when you feel you have the most energy. You can plan your eating at these times even if it’s not your usual mealtime.

Diarrhoea or constipation

You should discuss any changes to your bowel habit with the team that are managing your cancer. The team may want to check what is causing the change in your bowels or prescribe you a medication. There are some diet changes you can make to help resolve constipation. Increasing your fluid intake and being as active as able will help. Try to increase the fibre in your diet with foods such as:

- Wholemeal food options

- Fruit and vegetables

- Beans and pulses.

Have a look at The British Dietetic Association Food fact Sheet ‘Fibre’ and ‘Fruit and Vegetables – how to get five-a-day’ Food Fact Sheet for more ideas on increasing your fibre.

If you have diarrhoea, it is important to drink plenty of liquids (at least 2 litres or 3½ pints a day) to replace the fluid lost with the diarrhoea.

Try to eat small, regular meals and reduce your fibre intake (see food list above) until the diarrhoea improves. Try to avoid very greasy or very spicy foods. Some people may need to take a low fibre or low residue diet when your bowels aren't moving. This is usually only recommended if your cancer or tumour is blocking part of your gut. High fibre in your diet can make symptoms such as cramping and pain worse or can risk damaging your bowel. You should only follow this diet if your doctor, nurse or dietitian has advised you to.

Feeling sick

It is important that you let the team looking after know if you have been or are feeling sick. The team can then check the cause and give you the appropriate treatment. Eating when you are feeling sick can be very difficult. If you have vomited (been sick) the most important thing is to try keep your fluid intake up. You can keep your fluid intake up with small frequent sips. Drinking large cupfuls or glasses may make you feel more sick. If you can’t eat because you feel sick, avoiding cooking smells and avoiding hot meals and foods may help.

You can find lots of hints and tips for managing eating when you are feeling sick on Macmillan Cancer Support or Cancer Research UK websites.

Where can I get more help?

- Macmillan Cancer Support Eating Problems

- Cancer Research UK Diet Problems with Cancer.

Remember to speak with the team looking after you if any of these problems are lasting more than 24-48 hours.

For some people, cancer or treatment can leave you with symptoms that stop you eating the types of food you usually did. If this is the case you can ask the team looking after you for more advice or referral to a Dietitian. But if you have no symptoms or problems with eating (and you are a healthy weight for your height) then you should try to follow the government diet advice for general health and wellbeing.

The Eatwell guide helps you to understand the different food groups and the share of each food group you should include in your diet every day. The Eatwell Guide can be downloaded here so you can keep as a reference for yourself.